Adaptation, while a tricky subject, is necessary in bringing the written word to the screen. While the subjects tackled in my previous screenwriting posts are important for adaptations as well, you may find yourself in a bit of a corner, depending on how much freedom you have to make changes.

All in all, the only advice I can offer is what I've learned adapting older screenplays. So...

UPDATE! UPDATE! UPDATE! (AND BE AT LEAST A LITTLE P.C.)

One example is the subject of drunk and impaired driving. As recent as the late-90s, many jurisdictions didn't punish drunk driving causing death on a similar level as murder or other crimes causing death. But after that, the laws changed fast, and public perception, attitudes, education, and efforts did so in turn, turning what was once considered lighthearted comedic fodder (like in 1981's Arthur) into a notion downright horrifying (in, well, real life...). Many films before this time seemingly either didn't bother with the ramifications of driving impaired, or characters didn't take the dangers of it seriously. If this at all comes up in your source material regarding your "hero", my advice is to either frame it as wrong or cut it out entirely, since unpunished impaired driving is a real easy way for your audience to lose sympathy, no matter what era it's set in or how normalized it is.

CULTURALLY TRANSLATE (AND WITH DETAIL)

This is especially true if your adaptation is set in a different location. Even neighboring countries like the U.S. and Canada can have vastly different attitudes in many areas, from the large sociopolitical to the tiny, tiny, regional. For example, if a story set in the concrete jungle of N.Y.C. is transported to Nanaimo, B.C. (even barring a half-century of time and progress), the differences would be downright staggering.

For one, a population of millions is now whittled down to less than 100,000. That alone affects characters' habits, annoyances, social circles, the works. Also, while Nanaimo's business sector in many fields is growing, it's still a town of blue-collar, construction, forestry, fishing, and other industries. Being a "small city, with a small-town feel" will also inform characters' dispositions for a number of reasons.

And then there's the weather. Nanaimo, like much of B.C.'s rainforest, is mild and wet for much of the year. As attractive as the visual may be, a convertible is not terribly practical for this reason, so a hardtop Mustang it is instead. Spread out between the older "South End" and newer "North End", Nanaimo is a city that demands driving for most people, unlike many in N.Y.C., and the presence of forests, mountains, rivers, and other natural features would play into how the city presents itself to people.

Basically, with these two first headings, when you adapt, do your research first.

EXPLORE AND "FILL IN THE BLANKS"

Are you curious about a character's personal life that didn't get much focus the first time? Are you wondering about an unexplained character detail that would be seen as a cause for concern today? Are you more aware of a societal issue or theme than the author and their time period were and want to incorporate that? If you're allowed to, this is a great way to flesh out your material.

Did your protagonist mention having a mother in your source material? You might then choose to create a backstory for your protagonist, where he grew up witnessing his mother being beaten by his often-absent, alcoholic father, and after said father's sudden death, your protagonist devoted himself to helping his mother rebuild her life. How much your new material plays into the story's main events is up to you, but it's a great way to inform a character beyond a mere archetype (or worse, a blank slate).

This can also apply to factors such as setting. For example, does your setting change require a longer distance between locations? Put that into the script, and see what happens. In a comedy, this could lead to new comedic possibilities with these new situations.

CHANGE THE PERSPECTIVE (IF EVEN JUST A LITTLE)

Similar to the above, does a deuteragonist feel "pushed to the sidelines" to you? A way to round out the story, should you choose, is to slightly alter the story's perspective to include this deuteragonist's for a more even-handed approach. This is often done if the deuteragonist was merely the inactive narrator in a novel, in an attempt to give them more to do onscreen.

Conversely, if you feel your source material is too crowded (especially in a novel), you might be better off streamlining the story to one main relationship, possibly with minor subplots, to keep focus, especially on the emotional core of the story you want to keep intact.

IF NOTHING ELSE, KEEP TO THE EMOTIONAL SIDE

Film is made for the emotions that can't be stated in just words, so stated exposition, for example, is usually better off shown than told. Not everything has to be shown, if a given example can save time as just a single line of dialogue instead, but keeping to a story's emotional side is a good "cheat" for your audience to at least empathize with the characters. What looks do they give? What do they say? What don't they say? How do they feel? Avoid cold, bland, emotionless information when you can.

THINK ABOUT THE CORE MESSAGE (AND WHETHER IT SHOULD BE CHANGED)

This relates to all the other points above, but this is imperative when considering the direction you yourself want to take. How does the sentiment put forward by the author hold up? Is it tired? Dated? Problematic? Open to a dozen opposing arguments? Should it be flipped on its head to discover a new, more inclusive core message? Like in a new script and story, this should ideally be decided early on, in order to set the tone for your adaptation.

For example, 1997's Starship Troopers casts its more pro-military source material in such a darkly satirical way, it's virtually "ahead of its time" in using traditionally-fascist imagery to criticize America's military-industrial complex, among other things.

Sometimes, it's just a matter of reversing the argument put forward by the author that will yield some great potential.

IF YOU DO MAKE CHANGES, SUPPORT THEM

This will definitely take some time, and for good reason, since this is an aspect that the audience's suspension of disbelief can hinge on. Many film adaptations have "artifacts" of characters, plotlines, subplots, etc. that have been excised in the adaptation process. So with each change you do decide to make, think them through and consider their ramifications, which will likely run through the rest of the work.

In Death on the Nile, Rosalie Otterbourne falls for Tim Allerton,

gaining the mother figure she never had in Tim's mother.

The 1978 film adaptation excised the Allertons completely and

paired Rosalie with Ferguson instead, but gave little support

to their relationship at all.

In the novel, Linnet was well-meaning, had a sheltered upbringing

due to her wealth, and eventually realized how much she had

hurt Jackie in stealing Simon from her. The 1978 film cuts virtually

all of this, likely souring any sympathy the audience would have for her.

Even through little character and dialogue details, you can fill any holes left in your script by your changes. Had Linnet been kinder to her household staff and those working on the Karnak (or expressed more concern for her maid Louise, given what the latter wanted to do), it would have opened her character up to interpretation like the novel did, while still showing the tragedy of her murder.

Even if your changes are simply detail-oriented rather than quantity-oriented, think back, ahead, and thoroughly about how the rest of the work will be affected by it.

Should you take the approach of 1982's Evil Under the Sun and combine characters, it's important to think in terms of "dualities" rather than individual traits.

Combining two seemingly-opposite characters

from the novel was a brilliant move by Anthony Shaffer.

Being played by Maggie Smith also helps.

Now I say making changes and smoothing them out takes time, since this is likely the approach the original author took in writing the source material. Character traits/dualities/actions/dynamics inform everything they do, so it's best to dedicate time to "testing" all of your changes, in hopes of keeping any "seams" between the old and new material from distractingly poking through.

Poochie: A change not at all smoothed out.

Adaptations are an excellent way for writers to dissect works down to the last detail, to recognize what makes them work, and to recognize that (as stated by Pixar's "22 Rules of Storytelling") what they like about them is a part of themselves. This will not only sharpen your analytical skills, but also help you recognize the universally-appealing emotional cores you want to take into your own stories and scripts.

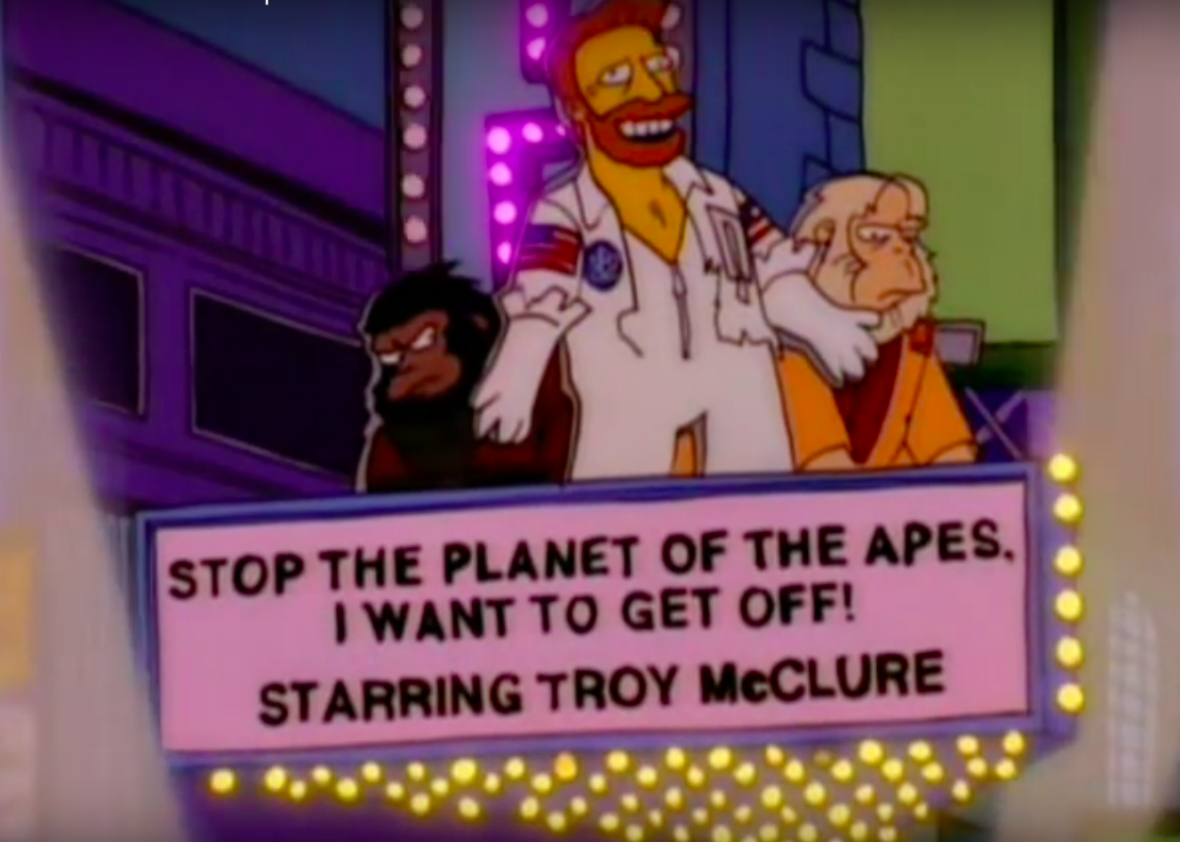

I didn't think this screencap fit under any of the

headings, so I thought I'd just stick it here.

No comments:

Post a Comment